This week I would like to discuss the clinical science of Epidermoid Brain Tumors. I hope to delve into what is known about this condition, however, it should by no means serve as a reference guide to these tumors. I will format this article like many medical publications format their data. I feel this format best highlights the salient points and is most appropriate for a discussion on the scientific background of epidermoid tumors. You can blame my many years of reading solely medical literature but I have formatted this article like a medical article with sections like: Definition, Epidemiology, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Special Cases, and Treatment.

I am typically very inquisitive by nature; if I see or read about something new to me, I’ll immediately try to gather as much information on the subject that I can. However, when I was diagnosed with a ‘probable Epidermoid Tumor’[1], I deliberately did not research the topic. I wanted to know as little as possible before undergoing surgery – maybe I was afraid of what I’d come across, or maybe I was simply too preoccupied with family and friends to have the time to delve into the condition, but regardless of the reason for my purposeful ignorance, the end result was the same: a confirmed diagnosis of an Epidermoid Tumor and a forever changed life.

It was not until several weeks ago that I finally performed a formal ‘literature search’ of Epidermoid Tumors. The search returned over 200 articles of medical literature detailing the condition. However, this number is misleading as many of these articles were of little use to me (i.e.: case reports[2], studies of Epidermoid Tumors on animals, rare gene mutations surrounding the tumor). While each and every publication has its significance, my aim to provide you with an overview of the tumor did not require these details. The important take-away of this search is that it revealed something I had long suspected: even though this tumor has been around for a very (very) long time (see this amazing article at http://anthropology.net/2009/06/15/first-neanderthal-fossil-dredged-from-north-sea/), little is still known about the tumor. Allow me to attempt to summarize what I found:

– – – Definition – – –

Epidermoid Tumors are benign cysts that typically develop in either the brain (intracranial) or in the spine.[3] It is a congenital tumor, meaning it is present at birth. It is postulated that the tumor begins its growth between the 3rd and 5th weeks of life (in the womb).[4] The tumor arises from an abnormal growth of epithelial cells (a type of animal tissue) and is sometimes called ‘pearly tumors’ because of its white, curdy appearance.[5]

– – – Epidemiology – – –

This section centers around demographics of the tumor. It is estimated that 0.3 – 1.8% of all intracranial brain tumors are Epidermoids.[6] In some studies, albeit small ones, there is a slight female preponderance.[7] The tumor seems to like the back of the skull, with an estimated 37.3% of these tumors located in the back part of the brain.[8] What I’ve given you above are numbers; figures that reflect statistics found in studies, take these numbers with a grain of salt as really this tumor, although rare, can effect anyone, anywhere.

– – – Symptoms – – –

Describing the symptoms patients may experience as a result of this tumor is tough because the tumor can have such a wide array of effects. The most common symptom described is headache.[9] In fact, a published case study describes a patient with specific headache symptoms (called Trigeminal Neuralgia) who actually was suffering from an Epidermoid Tumor.[10] The reason I tell you that these symptoms are hard to describe is because symptoms really depend on where the tumor is located. These can range from conditions as severe as seizures to something as benign as taste difficulties. There are many nerves (some called cranial nerves) that pass through this area making themselves vulnerable to being pushed on by the tumor. For me, I awoke one morning with double vision. This became worse until I finally told my Family Doctor about it, who obtained an MRI.

The bottom line is that because the symptoms are so varied, the diagnosis cannot be made solely on the basis of symptoms and physician evaluation. By no means does everyone suffering from a headache have an Epidermoid Tumor, but this is when the clinician must pick up on other clues to facilitate further investigation or imaging, such as an MRI or neurological referral. This is an ideal segue to the next section, ‘Diagnosis.’

– – – Diagnosis – – –

As I alluded to above, because symptoms are so varied, imaging is needed to aid in the diagnosis. Unfortunately, this tumor does not show up on regular x-rays. (In the past, the only way for it to be seen on x-ray is when the tumor grew enough to erode the skull bone).

In medicine, it is generally accepted that Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is superior to Computed Tomography (CT) when examining masses. There are reasons why CT is used over MRI in many instances: CTs are more sensitive at picking up bleeding in the brain, can be performed quicker, and cheaper, and any metal in your body (i.e. a pacemaker) precludes you from having an MRI done. Epidermoid Tumors can be seen on CT, however, MRI is still a more accurate means of visualizing the mass. It pains me to say this, but there are some health insurances that require the patient to get regular x-rays before they will cover an MRI.

While MRI can point you (and your clinician) towards the direction of an Epidermoid Tumor, actually looking at the tumor under a microscope is needed for a diagnosis. The medical school adage, ‘tissue is the issue’ (for some reason doctors like phrases that rhyme) holds true here. As I was told by my neurosurgeon before my surgery, “I can tell you that it’s probably an Epidermoid Tumor based on the MRI, but there is no way for me to be sure without actually going in, taking it out, and having a pathologist look at it.”

– – – Treatment – – –

Treatment for these tumors is typically surgical. This comes with a caveat: brain surgery is an incredibly invasive surgery, thus if it can be avoided you and your surgeon will elect against it. For this group of patients, a wait and watch approach is taken. The tumor is closely monitored by MRI for signs of growth. The interval for this surveillance is typically yearly with variations depending on clinician comfort and overall gestalt. But symptoms always trump the MRI. For example, if you began developing debilitating headaches as a result of the tumor, your surgeon will advise you to have surgery to remove the mass, regardless of its MRI appearance.

Unfortunately, there are no special medications that can shrink the tumor. Any medication given is typically to aid with symptoms, these do not serve the purpose of treating the tumor itself.

– – – Special Cases – – –

There are a few special cases to note:

First off, what is to be done for Epidermoids in pregnancy? Generally speaking, for both the health of the mother and fetus, surgery is avoided in child bearing women. However, there are some instances where surgery cannot wait and be put off until after delivery, in these extreme cases surgery is undertaken. Studies have shown good success in these cases, as the surgery does not involve the abdominal cavity.[11]

Also, I mentioned above that this is a tumor of epithelial cells (a type of tissue) and because of this transformation of this tumor from a benign to a malignant one is an occurrence that must be mentioned.[12] This is an incredibly rare event (on the order of hundredths of a percent), but you should know that the tumor can potentially become a Squamous Cell Carcinoma (a big term for cancer).[13]

– – – Questions to Ask – – –

When faced with this diagnosis, it is important to ask pertinent questions. It can be a difficult to do at the time. I remember being told there was a large mass in my brain, but then after that everything else was a blur. I know that I was so shocked with the news that I did not ask any questions, let alone pertinent ones. This is usually a diagnosis that comes out of nowhere, thus if you need time to compute and comprehend it, then ask and inquire at a later time. Remember, this is your health and body. It is also a slow growing tumor, so time is your ally. For some, like myself, time is needed to come to grips with what is going on. Go home, research the tumor, and either return to the Neurosurgeon’s office or telephone them with your questions. Here are some of the questions I wished I would have asked:

The first decision point made in the Neurosurgeon’s mind is whether or not surgery is needed. Thus I will divide the questions to ask based on the decision to undergo or forgo surgery:

Surgery questions:

- What are the risks of surgery? (Your surgeon will inevitably give you the generic risks of surgery i.e. infection, blood loss, death; but are there risks specific to this surgery? My surgeon warned me of possible ensuing Cerebellar Mutism, a rare complication of surgery in this area of the brain, where the patient is unable to speak for several months after the surgery).

- What is your experience in this area? Even though the tumor is rare, it is possible to find surgeons with more (or less) experience in the tumor’s location.

- What should I expect with the recovery process? Will I be in an Intensive Care Unit following the surgery? How long should I expect to be absent from work?

- What kind of surgical approach will you be taking? (The number of new surgical approaches changes by the minute, thus it’s important to know which one your Neurosurgeon will be taking).

- I’ve read that this tumor is often contained in a capsule. If this tumor is in a capsule that’s tightly adhered to the surrounding area, how aggressive in its removal will you be?

- After the surgery, how often will I be monitored for recurrence?

Wait and Watch Questions:

- How often will you be monitoring this tumor?

- Based on this tumor’s location, what symptoms should I look out for?

- Will the monitoring be done by you? (Or a Family Physician or Neurologist)

- What is your threshold to proceed to surgery?

- In your experience, what is the likelihood that my tumor will ultimately require surgery?

I understand that this diagnosis usually comes in the form of a whirlwind, and that my telling you to compose yourself to think about the diagnosis and its implications is easy in hindsight. But realize that you have time on your side. Remember this is your health, and you are your own best advocate.

[1] An image, like an MRI, cannot give you a definite diagnosis. It can only (at best) strongly suggest a diagnosis.

[2] A Case Report is an article about a single case.

[3] Epidermoid, Dermoid and Neuroenteric Cysts. Youmans Neurological Surgery, 6th ed. Chapter 136, p 1523

[4] Id

[5] An Analysis of Intracranial Epidermoid Tumors with Malignant Transformation: Treatment and Outcomes. Nagasawa, DT, Choy, W. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2013, p1071.

[6] Intracerebral Epidermoid Tumor: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Iaconetta, G, Carvalho, G et al. Surg. Neurology. 2001, p218-222.

[7] Id, p220

[8] Id.

[9] Epidermoid, Dermoid and Neuroenteric Cysts. Youmans Neurological Surgery, 6th ed. Chapter 136, p 1523

[10] Epidermoid Tumor Presenting with Trigeminal Neuralgia and Ipsilateral Hemifacial Spasm: A Case Report. Otsuka, S, Nakatsu, S et al. Archive for Japanese Surgery. 1989, p245-249.

[11] Management Strategy for Brain Tumour Diagnosed During Pregnancy. Lynch, J, Gouvea, F et al. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011, p225-230

[12] Intracranial Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in an Epidermoid Cyst. Acciarri, N, Padovani, R, et al. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 1993, p 565- 569.

[13] An Analysis of Intracranial Epidermoid Tumors with Malignant Transformation: Treatment and Outcomes. Nagasawa, DT, Choy, W. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2013, p1071-1078.

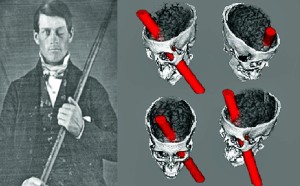

school we are introduced to the incredible story of Phineas Gage. On September 13 of 1848, Gage, working as a foreman for a railroad, underwent a horrific accident that resulted in an iron rod piercing through his left eye socket into his brain and out through his skull. His story is an incredible one because not only did Gage live through this incident, but he became a productive member of society afterwards.[6] In considering brain injuries and their effects, we should think about the story of Gage. He reminds us of the power of the mind and its ability to overcome the greatest challenges.

school we are introduced to the incredible story of Phineas Gage. On September 13 of 1848, Gage, working as a foreman for a railroad, underwent a horrific accident that resulted in an iron rod piercing through his left eye socket into his brain and out through his skull. His story is an incredible one because not only did Gage live through this incident, but he became a productive member of society afterwards.[6] In considering brain injuries and their effects, we should think about the story of Gage. He reminds us of the power of the mind and its ability to overcome the greatest challenges.

r the challenges this tumor carries with it?” While the physical challenges can often be overcome with time in the gym and/or medicine, the mental hurdles are ones that no medicine or sweat can fix. It is a battle that many of us do not foresee, but in order to re-enter into our lives completely, it is a battle that we must win.

r the challenges this tumor carries with it?” While the physical challenges can often be overcome with time in the gym and/or medicine, the mental hurdles are ones that no medicine or sweat can fix. It is a battle that many of us do not foresee, but in order to re-enter into our lives completely, it is a battle that we must win.